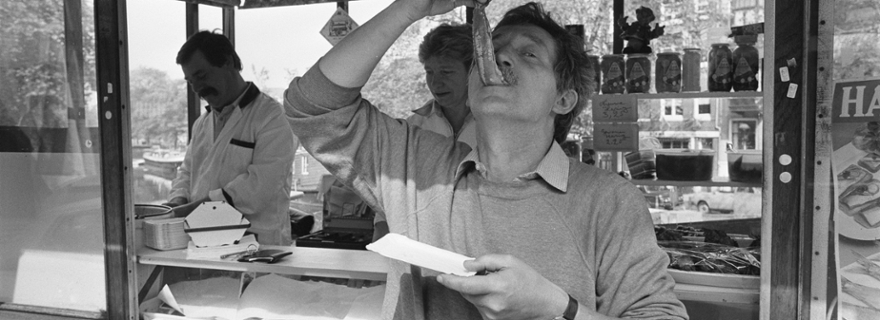

You should eat herring on the coast and not in Maastricht

For thirty years, the Dutch Newspaper AD conducted an annual search for the best herring. This came to an end when economist Ben Vollaard, based on a statistical analysis, claimed it was rigged. But that claim doesn't smell right, says Leiden statistician Richard Gill. ‘The way you code and process data can have a big effect on the outcome of an analysis.’

For the herring test, the AD visited about 100 fish shops each year to taste and review the herring. Getting into the top ten is a nice payoff for a shop. ‘It's a bit like a Michelin star, but for herring,’ says Gill. ‘Fish shops can put themselves forward when they think they deserve a place in the rankings. A sign saying you are among the best in the Netherlands, is a rewarding prize.’

It was rumoured among fishmongers that the test was a sham. ‘Especially among the herring sellers who scored poorly,’ Gill says. That gossip became big news when Tilburg economist Ben Vollaard published a statistical analysis that suggested fraud in the results. That concerned two things. First, the AD itself is Rotterdam-based and fish shops in Rotterdam would have gotten higher scores. The second rumour Vollaards wanted to prove was that shops that bought their fish from wholesaler Atlantic, also had received a higher score. ‘One of the herring testers had in fact advised this company as a consultant and also gave courses on how to fillet and cut herring correctly.’

No causality, but yet convinced of fraud

With his statistical analysis, the economist wanted to show that the jury's assessment of the herring did not match the final ranking. Media from all over the country were diving right on top of this. ‘It was in all the newspapers and Vollaard was even a guest on the famous Dutch talkshow De Wereld Draait Door. There he did cover himself by repeatedly saying he had found a correlation and not a causation. This means he found a statistical correlation, but no proof that one variable has an influence on the other. But at the same time, he also said that he believed there was something fishy about the case.’

The AD took issue with the accusations and filed a scientific integrity complaint against Vollaard. Tilburg University, Vollaard’s employer, decided that scientific integrity had not been violated. But the AD did not leave it at that and took the complaint to the National Institution for Scientific Integrity (LOWI). ‘It is the equivalent to an appeal in a court case.’ It is at that point that Gill got involved. ‘They asked me to assist them as an expert.’

Under further investigation

Gill closely examined Vollaard's statistical analysis and immediately had questions. 'It was an incorrect form of statistics that had not been carried out by a statistician.’ Gill wrote a report and LOWI eventually concluded that there was no deliberate violation of scientific integrity. ‘However, the committee did decide that there were scientific questions to investigate further.’

After his report, the herring story did not let Gill go. ‘There are a lot of things about it that make the elementary kind of statistics that had been applied to the data completely wrong. The herring shops either signed up themselves or were signed up by customers. So the data is not a random sample, but a self-selecting sample. That can cause huge bias.’ And that was just one of many things that caused the analysis to be wrong. ‘The relationships are sometimes so weak that a small change in the way you code the scores (0-10) gives a big effect. You can turn an 8+ into either an 8, an 8.1 or an 8.8, for example. That difference is huge in statistical analysis.’

‘That is an important conclusion, even if it is a negative one. The conclusion that you can’t conclude anything from data is also incredibly important. That’s what statisticians are for.’

Herring shops pop up further and further from shore

Gill and his colleague Fengnan Gao examined all the data thoroughly and redid the statistical analyses. And what did they find? There is no causal relationship and therefore no statistical reason from which to infer fraud. ‘That is an important conclusion, even if it is a negative one. The conclusion that you can’t conclude anything from data is also incredibly important. That’s what statisticians are for.’

Gill and Gao did find a geological influence. ‘If you compare similar shops at different locations in the country, the herring along the North Sea coast scores better.’ Yet that does not mean there is a causal relationship. 'You have to properly separate the effects of different things. For example, we see that the new participants in the test are further and further away from the coast. These are shops that are starting up and want to make a name by participating in the herring test. And new shops may just not yet be as good as the herring farmers who have been doing it for years. Added to this is the fact that competition on the coast is huge. That too can have a positive effect on quality.’

Herring tastes better by the sea

And what about the higher scores for companies that buy their fish from wholesaler Atlantic? ‘Atlantic’s fish generally does well, possibly also because there is a very professional company behind it that advises very well how it should be done. But not all shops with fish from Atlantic do better than shops that buy it elsewhere. Especially if you look at the inland businesses supplied by Atlantic. They too are not doing as well as those at the coast.’

After years of statistical research on herring, Gill himself still likes a good fish. ‘I’ve tasted a lot of herring in different places over the past few years. I like the new-season Dutch herring: Hollandse Nieuwe, very much.’ He himself usually eats herring at the market in Apeldoorn, but after his research, he knows where to go best. ‘By the sea, it should taste better. The setting by the dunes definitely contributes to that too,’ he laughs. ‘But I wouldn't recommend eating Hollandse Nieuwe in Maastricht.’

Richard Gill and Fengnan Gao's research has been published in the Scandinavian Journal of Statistics and will also soon appear in the journal Significance.