Eric Jorink: 'We want to map the tradition of observations'

The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research has awarded a grant of 750,000 euros to the 'Visualising the Unknown in 17th-century Science and Society' project. Researchers will reconstruct how seventeenth-century scientists recorded and shared their groundbreaking microscopic discoveries. We spoke with project leader and professor by special appointment of Enlightenment and Religion Eric Jorink about the project and its contemporary relevance.

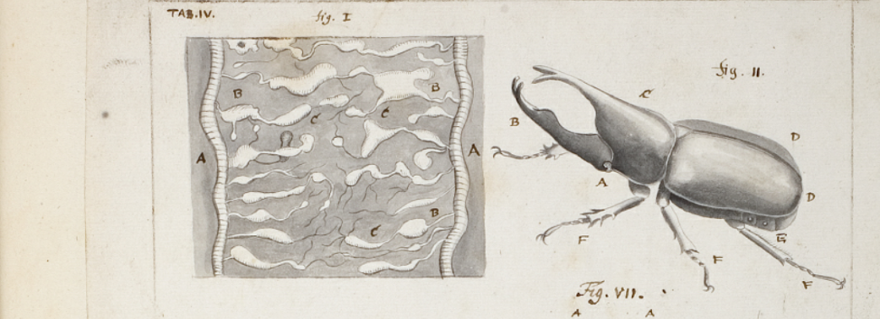

It was in the seventeenth century that scientists first used the microscope to look at previously unknown life forms, such as bacteria and sperm. 'If you don't know what you are looking at, it’s very difficult to determine what you are seeing,' Jorink explains. 'Have you ever looked through a microscope? It’s just a big mess. It is difficult to convert that into an image because nobody had a visual frame of reference of a bacterium.'

The seventeenth-century scientists had to develop new techniques to understand, record, and communicate their discoveries. 'What we want to do is to map the tradition of observations. There is a contrast between what is written in the biology books and what you see under the microscope. Certain things are shaded, some are given a shadow, and some have nothing at all. Other things are blown out of proportion or omitted. We’re going to investigate these techniques.'

Importance of images

'We want to show how important images are in science,' Jorink continues. ‘Everyone can certainly remember last year: everyone was talking about the new coronavirus and no one knew exactly how it worked, but in February everyone already knew more or less what the virus looked like: a ball with spikes. The image precedes the knowledge. If you flip through a scientific magazine, you see all kinds of images, but there is no mention of how such an image came about.'

Art and science

To reconstruct that ‘how’, a combination of art and science is used. 'We’re going to repeat the very first experiments of scientists like Van Leeuwenhoek using original Van Leeuwenhoek microscopes. This way, we can see for ourselves what they could see and how they expressed it,' says Jorink. A scientific illustrator and photographer will develop the images. The scientists will use this interdisciplinary approach to try to answer a number of questions: 'How do you convince people that what you see actually exists? How do you make something like that credible? The history of science is much more than just who made the first discovery and where it was written down. It is also about how the discovery was made, who it was shared with and how it was communicated.'

He already knows how he is going to present the results of his research. Two exhibitions will be held about the research: one at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and one at the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave in Leiden. 'We specifically want to involve the public,' says Jorink.

The project 'Visualizing the Unknown in 17th-century Science and Society' is a collaboration between Huygens ING (KNAW), Bibliotheca Hertziana-Max Planck Institute for Art History in Rome and Rijksmuseum Boerhaave, Leiden. The Royal Society of London and Rijksmuseum Amsterdam are partners.