How a game can show that working together is essential in the nitrogen crisis

The Netherlands is embroiled in a complex nitrogen crisis. Berent Baris wants to use his NitroGenius game to demonstrate the complexity of this crisis. In the game, staff at the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality (LNV) take on the roles of different stakeholders.

Around ten members of staff at the Rural Areas and Nitrogen department at the Ministry of LNV have their laptops in front of them ready to play NitroGenius. The original game has been in existence for twenty years and is mainly used in higher education. Berent Baris, a researcher at the Institute for Environmental Sciences (CML), has completely updated the game so that it is relevant for the current situation. ‘The aim of NitroGenius is primarily to show the complexity of the crisis,’ Baris explains to the staff of the Ministry. ‘When a stakeholder makes a particular choice, that has an effect on other stakeholders.’

Making choices to reduce nitrogen

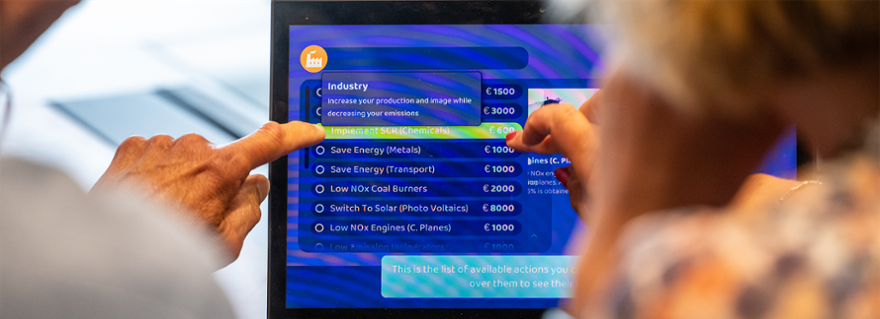

The aim of the simulation game is to collectively achieve the Nitrogen Act's target by 2030: 74% of the surface area of Natura 2000 areas, protected nature reserves, will by then have nitrogen deposition below the critical deposition value. Each player represents a stakeholder: agriculture, industry, government or consumers. They start in 2023 and each round consists of a year in which they have to make certain choices. For example, do the consumers choose to eat vegetarian or put solar panels on their roofs? Do agricultural entrepreneurs take measures to ensure their stables emit less NH3? Time and money are - as in real life - limited.

Everyone immediately takes on the roles they have been assigned and defends the interests of that role. A participant in the industry role commented, 'With my choices, nitrogen emissions are not lowering that much yet, but there is nothing wrong with my production, and that is of course important for me as an industry.’

-

Ministry of LNV employees play NitroGenius -

Berent Baris explains the NitroGenius game -

NitroGenius game -

Ministry of LNV employees play NitroGenius -

Ministry of LNV employees play NitroGenius

Tension toward 2030

As participants get closer to 2030, tensions start to rise. 'We are already in 2028 and have only protected 43%!' one participant cries. When asked why, he knows the answer: 'We haven’t worked together enough. We have put our own interests first. This game shows painfully clearly how important that is.’

And painful it certainly is. On average, the groups have protected about 50% of the areas from nitrogen deposition by 2030. Baris calls this scenario ‘the business as usual variant’. 'So this is what happens if we carry on as we are doing now, if we give too little consideration to each other's interests.' The question comes from the participants whether it is actually at all possible to achieve the 74% percentage. Professor of Environmental Sustainability Jan Willem Erisman, Baris’s supervisor during his master’s and the person who developed NitroGenius twenty years ago, replies that he and a group of students on oneoccasion achieved 83% protection. This was mainly due to measures taken in agriculture. He explains: 'Industry, government and consumers can take all kinds of measures, but if no measures are taken in agriculture, you will never reach the 74% protection.’

The Rural Areas and Nitrogen Department believes the game is inspiring. 'It is very insightful to think from other interests, and not only act from our job, from the viewpoint of government. The game shows that it is only if we work together, with all the stakeholders, that can we solve the nitrogen crisis.’

Baris is pleased that the participants are enthusiastic about the game. He hopes that eventually all kinds of organisations, municipalities and other parties will play his game to gain an insight into each other's interests. 'Hopefully, I won't have to update NitroGenius again in 10 years' time, because by then the nitrogen crisis will have been solved.'

Text: Nynke Smits

Photos: Monique Shaw