Deconstructing a more assertive China: How did its foreign policy change?

Since 2009-2010, the West viewed China as more assertive. Especially after Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, the country abandoned Deng Xiaoping’s ‘low profile’ foreign policy. Friso Stevens explains in his dissertation where this change has come from. The dissertation defence is on 28 March.

How did you come to study Chinese foreign policy, especially from a domestic politics perspective?

Stevens: 'After finishing my law degree, I started a second master's at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, specialising in international security studies. During my thesis research on the Chinese-American security dilemma, I discovered that the scholarly literature was mainly written from the US perspective on regional and world order. I was curious about the Chinese side of the story and was able to go to Beijing on a scholarship to study international relations. At Peking University, I was able to lay the foundations for my dissertation.

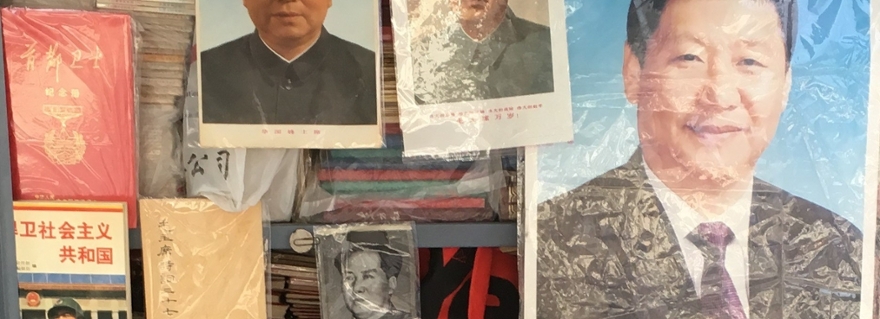

The essence of China’s long-held doctrine of ‘keeping a low profile,’ that was replaced in favor of a more forceful foreign policy, was to serve domestic economic interests. This was well described in 1990 by veteran diplomat Qian Qichen: ‘[Chinese] foreign policy is an extension of China's domestic policy. As China [strengthens] its economy and continues its reforms ... creating a stable, peaceful and favourable international environment is China's main task in the diplomatic sphere.’ Especially under Xi, Chinese foreign policy is all about employing China’s accumulated power to increase its regional influence.

When I returned in 2017, Frans-Paul van der Putten and Madeleine Hosli took me on as a PhD candidate. They were really great and I owe them a lot.’

You lived in Beijing for two years and then studied China for five more. Where did that fascination come from?

'I think my attempts to understand China and East Asia started when I visited Hong Kong in 2009. I like people and cultures that are very different from ours. In China, I like the informal and relational aspect, having to read between the lines. Chinese people are also quite open and curious about the outside world. Unfortunately, since the ramped-up Chinese nationalism during the Trump years, there is less interest in embracing Western ideas.'

What are notable findings of the study that you want to share?

'It is often forgotten in current conversations that relations between China and the US were excellent during the last Bush years. It was a period when Americans still saw free trade and the outsourcing of blue-collar jobs as something that benefited the US.

The same goes for the relationship between Mainland China and Taiwan. In December 2008, for example, direct air and sea links and a postal service were established for the first time. Although a distinct, Taiwanese identity was already emerging at the time, the US and Taiwan allowed Beijing to retain the hope that Taiwan could one day be reunited through these peaceful means.

Yet, China’s reaction to Obama’s ‘pivot to Asia’ is not the only explanation for Chinese assertiveness post-2008. A clear ideational path to the current conservative-nationalist line is visible. Indeed, back then, some of the same mobilisation slogans that Xi uses today were already being used. There is much more continuity between the Hu and Xi eras than the existing literature shows.'

Who should read your dissertation?

'The most obvious readers are those who study international relations and China and East Asia, members of think tanks, and policymakers in ministries. But I would also venture to say that Dutch journalists and opinion makers might benefit most from this work. I encourage them to make their own observations, instead of parroting American narratives and news stories. I wrote a Leiden blog about this earlier.

There is no doubt that China competes unfairly, spies, steals, and sometimes coerces. But this requires a defensive response, not an offensive one where Europe sends naval vessels to the other side of the world. The US’ ‘with us or against us’ leads us to an international system with Cold War-like blocs. That is a dangerous straitjacket to put yourself in. Europe can choose not to make China an enemy: that is certainly how China sees it.'

The promotion can be followed via a livestream