A podium for science

Rector Magnificus Carel Stolker will retire on 8 February. If there’s one theme running through his career, it’s the links between the University and society. In this series of pre-retirement discussions, Stolker will talk one last time to people from within and without the University. This edition is all about science communication, transferring knowledge and insights to a wide public. The guests: science communication researcher Julia Cramer and director of Rijksmuseum Boerhaave Amito Haarhuis.

It’s 5 January and a cold and foggy Leiden morning, the very same morning as the announcement that virologist Marion Koopmans and intensive care consultant Diederik Gommer have been awarded the 2020 Machiavelli Prize. This is special annual prize awarded to a person or organisation that has made an outstanding contribution to the communication between politics, government and society. This is the first time that the prize has gone to a scientist and a doctor. Well-deserved, Carel Stolker, Julia Cramer and Amito Haarhuis all agree.

Scientists in the media

Stolker reflects on the prize: ‘I follow Marion Koopmans on Twitter. Doubt and nuance are obviously part of her and other scientists’ DNA. Do people really understand that? I wonder what all the different scientists we have seen in the media over the past year have done to change people’s image of science.’ That is a difficult question to answer.

According to Julia Cramer, who conducts research into science communication at the Faculty of Science, you need a serious amount of courage as a scientist to appear on a talk show. ‘As a scientist you’re often sitting opposite someone who is very sure of themselves. But a scientist is more cautious, and all too aware of all that is still unknown about the topic. That makes you vulnerable, particularly on live TV. I think it’s really brave how Koopmans continues to engage with science sceptics.’

Faith in science

Haarhuis, who is a real practitioner of science communication at his museum, notes that at the beginning of the crisis politicians wanted to be led by science. ‘We’re listening to the science is how Rutte put it. I think that had a positive effect on public confidence. Compare it with the US, for example, where science was expressly excluded. I find that worrying. You can see how quickly things can go wrong and people lose confidence in science.’

‘What can a science museum do to buck this trend?’ Stolker asks.

‘That’s a really important question,’ says Haarhuis. ‘Demonstrating how important faith in science is, is at the heart of our mission as a museum. We do this by showing the role of science over the past five centuries, for example, and what kinds of discovery and innovation this has spawned. We have to help people keep up with scientific progress, particularly if things suddenly move so fast, like now with the development of the coronavirus vaccine.’

Instagram or Twitter

They continue to chat about coronavirus, vaccinations and above all Koopmans and Gommers’ contributions to the communication about the two. Stolker thinks it’s a bold and daring move by Gommers to start an Instagram account and embrace the associated communication style. ‘You don’t often see that with scientists. You sometimes see them on Twitter, but not Instagram.’

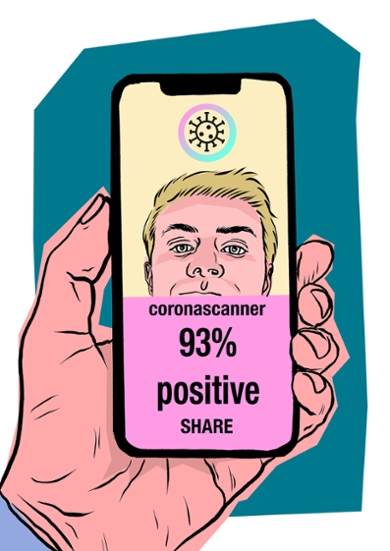

Haarhuis adds: ‘What also plays a role is the reaction of Gommers’ colleagues. Social media forces you to make your message short and therefore incomplete, and some scientists think you shouldn’t do that.’

The Sagan Effect, says Cramer. ‘Astronomer Carl Sagan did a lot of science communication and this probably meant that he missed out on a very important scientific accolade. Unfortunately, some academics think that popularisation is incompatible with being a good scientist. Hopefully that is now changing.’

Justification

Has the attitude of scientists towards communication changed in the time that Stolker has been Rector? ‘I still remember from my time as dean of the law faculty asking at some point whether PhD candidates would like to provide a short piece about their research for the website. They generally produced a summary of the summary that was on the last page. Completely unappealing. That has changed massively. We now talk to researchers and find it important to justify how we spend public money. A professor’s appointment is an investment of millions of euros. We have realised that we have to explain all that such a person does. There is more awareness of how important research really is. For us, but definitely for society too. And it gives the researcher confidence that his work really does count.’

Cramer: ‘When it comes to communication, researchers now see one another’s successes, also with grant applications, for instance. A funder is now more likely to ask you to spend some of your budget on communication or impact. I think that’s a really good thing.’

Astronomy exhibition

‘That you have to justify what you do with your money is something that astronomers, for instance, understand very well indeed,’ says Haarhuis. ‘They have really expensive equipment and are all too aware that society wants to see something in return. Their approach is something other disciplines can learn from. Take Ewine van Dishoeck. As guest curator she put on a fantastic exhibition together with our museum.’

Cramer agrees. ‘Communication is part and parcel of astronomy. That is gradually happening with other disciplines too.’

Explain to administrators

Stolker notes how important it is for academics to be able to explain their work to administrators too. ‘When I had just started as Rector, Ewine van Dishoeck came to me and said: “Carel, we have no idea whatsoever about 97 percent of the universe.” That really hit home with me. Eight years later she came back and said: “Carel, 96 percent of the universe is still a complete mystery.” That once again made an impression, but I did think: “At least there’s been some progress!” If you understand what a scientist is doing and can see their passion and the importance of what they’re doing, you’ll work harder as an administrator.’

Research in museums

As a researcher and a museum director are Cramer and Haarhuis of any use to each other, Stolker wants to know. ‘Definitely. There are lots of links and partnerships between the University and science museums,’ says Cramer. ‘For instance, the research of my colleague Anne Land-Zandstra, whose work includes the question of how important authenticity really is. How important is it for children that an object is real? Very important, apparently. The first thing they ask about a museum exhibit is always: “Is it real?’” If you can say yes, this really is an instrument that someone used long ago in an experiment, they are fascinated.’

Podium for science

The good thing about Leiden is that the four national museums that we have all developed from the private collections of Leiden professors,’ says Stolker. ‘The museums and University have become much closer recently. The collections are becoming more involved with the teaching, which is a great development.’

Haarhuis agrees: ‘A museum is not only about the past. It’s also our task to give science a podium. But you do need science history if you want to tell the full story, fascinate people and show how progress has been made.’

Text: Maarten Muns

Illustrations: Pirmin Rengers

Podcast: Carel Stolker on coronavirus, vlogging and the void

In a few weeks’ time Carel Stolker will be retiring as Rector Magnificus. In a double episode of the Science Shots podcast, we take stock: what were the key lessons, how has the coronavirus crisis been and of course, what will he do to avoid the post-retirement void? Stolker shares his experiences in a candid interview (in Dutch).