Healthy soil for a healthy gut

How does the soil we grow our vegetables in, affects the health of our gut? And does a healthy soil gives crops a better quality and taste? These are some of the questions Soil ecologist Emilia Hannula and a big consortium will work on. With an NWO-KIC grant of 1.8 million, CML, IBL, FGGA, the LUMC, farmers and institutions all over the Netherlands, will dig into the features of soil.

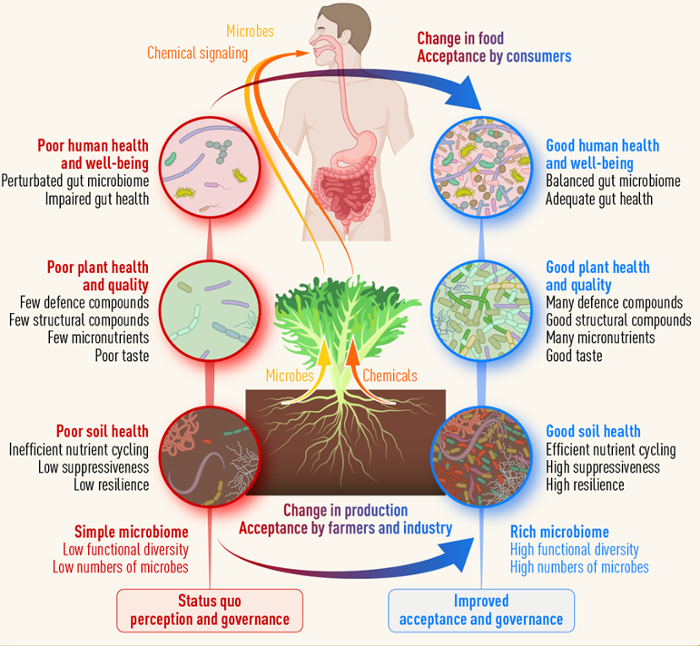

The common saying ‘You are what you eat’ might have more to it than we already knew. And not only what we eat, but also what soil we grow our food in, Hannula says. ‘In this project we want to look at our agricultural systems in a way that they become healthcare providers. We want to know how the treatment of the soil affects the micronutrients, metabolites and microbiome of the crops.’

The way farmers cultivate crops, most likely has a big impact on the diversity of these soil microbiomes. ‘In the past decades we have intensified our agriculture in order to have more profit from the same piece of land’, Hannula says. ‘Farmers have been using more pesticides and fertilisers. These kill part of the microbiomes and damage the health of the soil.’

Microbiomes in our gut

The researchers expect that eating crops from soil full of microbiomes, will have a positive effect on human health. ‘We need a sufficient number of microbes, such as bacteria, viruses and yeasts, in order to have a healthy gut. And we mainly get these out of the food we eat.’ A lack of these microbiomes causes an impaired health of the gut and results in diseases. ‘These are called non-communicable diseases (NCDs): diseases that are not spread through infection or through other people, but are typically caused by unhealthy behaviours. So the question is: if these diseases are caused by eating bad food, can we also reverse them by eating good food?’

The crops growing on highly cultivated land will most likely grow with fewer microbiomes and be less healthy, Hannula expects. ‘Simplified gut microbiomes cause gut diseases so the assaults to the soil might be directly linked to these diseases.’ And the treatment of the soil might have more consequences than health alone. ‘A soil with better quality, should yield better quality crops as well. That means crops grown in better soil, possibly taste better as well.’

Testing and tasting

To look at all these factors, the expertise of multiple universities and institutes is combined (see box). ‘First we will determine how different agricultural practices affect the soil microbiome. We have over fifty farmers participating at whom we can take samples. Next to that, we will also grow our own crops in a controlled environment.’

In the next step, researchers from IBL will compare the quality of crops depending on the way they are cultivated. ‘That involves the microbiomes, metabolites and nutritional properties. A professional panel, even with top chefs, will compare and evaluate the taste of the different crops.’ To bring everything together, the researchers will look at the medical side. ‘First we will test the in models that simulate the microbiome in a gut. Later, different diets will be given to people with gut diseases. Then we can compare the effects of a diet with vegetables from intensive agriculture and less intensive agriculture on the health of their gut.’

Paying more for healthy food

Gerard Breeman from the Faculty Governance and Global Affairs, is working on the project from a governmental perspective. If the project results in significant health effect related to different farming, the consortium will suggest governmental adaptations for the sector. ‘These are also favourable for the farmers. They are often open to change and want to know how to take better care of their soil and crops.’ And if research can prove that crops grown in less intensive agriculture encourages better health, the consumer might be willing to pay more for it. ‘Then it’s profitable for the farmer, more sustainable for the environment and better for human health.’

Hannula is very excited to be working on the project for the next six years. ‘In scientific research, we often only look at one part of the story. Now we will be able to take all aspects into account. That will be extremely interesting.’ She expects that this research might have a big impact on both society and science. ‘I’ve been into soil my whole career, but by working together, we have the opportunity to frame it into a bigger picture.’

The interdisciplinary consortium includes partners from Leiden University, the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC), the University of Groningen, the Van Hall Larenstein University of Applied Sciences, the Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW), farmers, consumers and companies. By combining all the expertise they hope to fully cover all perspectives of the subject. This includes: improving consumer health, improving soil health and agricultural sustainability, and ensuring economic well-being for farmers.